Lifting the curtain on the 20th century: the metamorphoses of Richard Strauss

An allegory in four acts

This is a final, revised version of a piece I originally posted here in four parts, under the title “How middlebrow triumphs over death.”

Act 1 The curtain rises

"When the clarinet slithers up a disjointed scale at the outset of the piece," writes The New Yorker's opera critic Alex Ross, "the curtain effectively goes up on twentieth-century music."

The piece in question is Richard Strauss's opera Salome, which had its world première at the Semper Opernhaus in Dresden on December 9, 1905. Like Igor Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, which caused a (literal) riot when it made its debut at Paris’s Théâtre des Champs-Elysées eight years later on May 29, 1913, Salome was a succès de scandale. This was not just because of the modernist dissonance of its musical score.

The first Salome, soprano Marie Wittich, found Strauss's reworking of Oscar Wilde's notorious 1891 play "distasteful and obscene." She flat out refused to perform the Dance of the Seven Veils—a professional dancer took her place, as would become the norm in many later productions—or to kiss the severed head of John the Baptist at the climax of the opera. "I won't do it, I'm a decent woman," she protested.

The audience had no such scruples. “It was received with unbounded enthusiasm,” Lawrence Gilman informed readers of The North American Review:

There were thirty-eight recalls for the singers, the conductor and the composer, when the curtain fell after the brief performance (the work lasts but an hour and a half). Since then, it has traversed the operatic stages of the Continent in a manner little short of triumphal. It has been jubilantly acclaimed as an epoch-making masterwork, and virulently denounced as a subversive and preposterous aberration: yet it has everywhere been eagerly listened to and clamorously discussed.

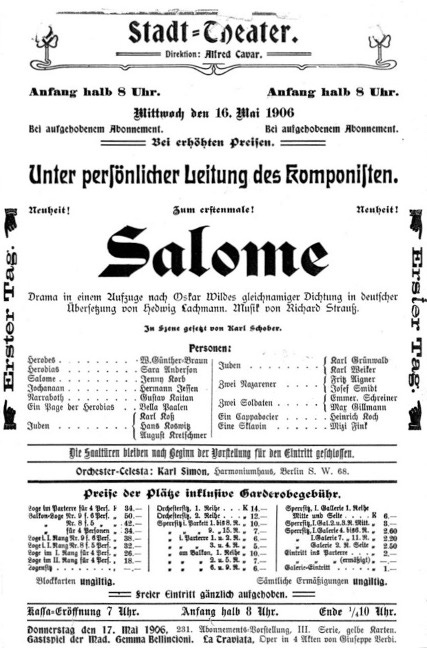

Over the next two years Salome was staged in more than fifty European opera houses. Having been banned by the censor in Vienna (where it was not performed until 1918), it had its Austrian première at the Stadtteater in Graz on May 16, 1906. Such was its allure that Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, Giacomo Puccini, and Alban Berg (and according to Richard Strauss, the young Adolf Hitler) were all in the Graz audience.

Salome’s New World première took place at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York on January 22, 1907, with Olive Fremstad in the title role. According to the Met’s chief archivist Peter Clark, Fremstad was "a daring Salome ... perhaps too daring in her fondling the severed head of John the Baptist." Two days later, the New York Times carried a letter from an eminent psychologist castigating Strauss’s opera as

a detailed and explicit exposition of the most horrible, disgusting, revolting features of degeneracy (using the word now in its customary social, sexual significance) I have ever heard, read of, or imagined ... the fact that it is phrased in limpid language and sung to emotion-liberating music does not make it any the less ghastly to the sane man or woman with normal generic instincts.

Banker J. Pierpoint Morgan's daughter Anne, who is nowadays remembered as a pioneering feminist and member of the “Mink Brigade” of wealthy society ladies who supported the New York garment workers’ strike of 1909, was equally distressed by the opera’s immorality. Luckily Daddy sat on the Met board. Five days later Salome was pulled as "detrimental to the best interests of the Metropolitan Opera House."

The lone performance and abrupt cancelation of Strauss’s opera may not have been the only factor in the wave of “Salomania” (as the New York Times baptized it) that swept the US in 1907-9, but it certainly helped things along. Before long a Salome dance craze was conquering burlesque and vaudeville stages across the nation.

Never one to miss the opportunity to document a popular trend, the painter Robert Henri, founder of the Ashcan School, hired a vaudeville dancer to model Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils for him in the privacy of his studio. He painted two versions of Salome Dancer in 1909, which today hang at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College and the Ringling Museum of Art in Saratosa, Florida. One critic wrote:

Her long legs thrust out with strutting sexual arrogance and glint through the over-brushed back veil. It has far more oomph than hundreds of virginal, genteel muses, painted by American academics. [Henri] has given it urgency with slashing brush marks and strong tonal contrasts. He’s learned from Winslow Homer, from Édouard Manet, and from the vulgarity of Frans Hals.

Others were less enamoured of this salacious European import. The actress Marie Cahill, who had previously “startled Broadway by entering a strong protest to theatrical managers against compelling chorus girls to wear tights and excessively short skirts against their will,” wrote to Teddy Roosevelt and other political leaders in August 1908 demanding “the establishment in the state of New York of a commission with powers of censorship over the dramatic stage.” She recommended the “very successful” Lord Chancellor’s censorship of London theaters as a model to follow.

Her fear, she said, was “for the young and innocent,” in particular “the large body of foreign youths and girls” thronging the city:

Is it not the duty … of the true citizen to protect the young from the contamination of such theatrical offerings as clothe pernicious subjects of the ‘Salome’ kind in a boasted artistic atmosphere, but which are really only an excuse for the most vulgar exhibition that this country has ever been called upon to tolerate?

The New York Times took a lighter view, reassuring its readers that “In spite of rumors which have been prevalent of late, it is extremely improbable that a ‘Salome’ dance will be substituted for the ‘Merry Widow’ waltz at the New Amsterdam.”

It is announced on good authority that the management there has been exceptionally active in guarding against outbreaks of Salomania among members of the company. As soon as any chorus girl shows the very first symptoms of the disease she is at once enveloped in a fur coat—the most efficacious safeguard known against the Salome dance—and hurriedly isolated.

Irving Berlin, who was then working as a waiter at Jimmy Kelly’s on Union Square, had his first hit with a little ditty called Sadie Salome (Go home!). There is a fine recording of him singing it with a mock Yiddish accent. The song was popularized by eighteen-year-old Fanny Brice, the original funny girl, in Max Spiegel's burlesque musical The College Girls, in which she performed a spoof of Salome dancing. Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr. saw the show and immediately hired Fanny for his Follies of 1910.

It’s nice to know that the opera whose opening chords raised the curtain on twentieth-century music was indirectly responsible for Irving Berlin getting his first job in Tin Pan Alley and Fanny Brice joining the Ziegfeld Follies. But Irving’s story of a good Jewish girl gone to the bad confirmed all Marie Cahill’s worst fears:

Sadie Cohen left her happy home

To become an actress lady

On the stage she soon became the rage

As the only real Salomy baby

When she came to town, her sweetheart Mose

Brought for her around a pretty rose

But he got an awful fright

When his Sadie came to sight

He stood up and yelled with all his might:

Refrain:

Don't do that dance, I tell you Sadie

That's not a bus'ness for a lady!

'Most ev'rybody knows

That I'm your loving Mose

Oy, Oy, Oy, Oy

Where is your clothes?

Act 2 The return of the repressed

Writing in the Brooklyn Eagle in 1926 from Paris, where Salome had by then long been recognized as “an opera that undoubtedly ranks in importance with the greatest works of the post-Wagnerian period,” Edward Cushing lamented that “the severed head of John the Baptist remained among properties blackballed by the moralistic indignation of a Powerful Few.” Salome would not be performed at the Met again until 1934.

Happily, New Yorkers with a taste for degeneracy were able to satisfy their perverse instincts when Salome was staged at Oscar Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera House in 1909, with the Scottish-born, Chicago-raised, Paris-trained soprano Mary Garden as Strauss’s lascivious heroine.

Famous for creating the leading role in Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande at the Opéra-Comique in 1902—she recorded a brief excerpt from Act 3 in 1904, accompanied by Debussy on the piano—Garden performed the Dance of the Seven Veils herself, stripping down to a bodystocking.

After Hammerstein’s opera company folded, Mary took her Salome to her hometown, reprising the role in the Chicago Grand Opera Company's inaugural season at the Auditorium Theater in 1910. The city's guardians of public morality were not pleased by what they heard and saw. The Chicago Tribune reported that patrons were ''oppressed and horrified. But of any real enjoyment, there was little or no evidence.''

The Tribune’s theater critic Percy Hammond seems nevertheless to have relished the star’s erotic writhings:

She is a fabulous she-thing playing with love and death—loathsome, mysterious, poisonous, slaking her slimy passion in the blood of her victim ... She is Salome according to the Wilde formulary—a monstrous oracle of beauty.

Like Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus or Courbet’s L’Origine du monde, Salome hits that sweet spot where highbrow and lowbrow meet and transmute base instinct into high art.

Chicago police chief Roy T. Stewart, who was invited to witness the spectacle for himself at the next showing, was having none of that. He threw his weight squarely behind the middlebrow:

It was disgusting. Miss Garden wallowed around like a cat in a bed of catnip. If the same show was produced on Halsted Street, the people would call it cheap, but over at the Auditorium they say it’s art.

Salome was scheduled for four performances—all of which were sold out in advance—but the company’s board of directors followed the Met’s moral compass and canceled the production after just three nights.

Back in the Old World, the Lord Chamberlain kept Salome off London's stages until Thomas Beecham negotiated a compromise that permitted a censored production to be staged at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden on December 8, 1910.

“We had successfully metamorphosed a lurid tale of love and revenge into a comforting sermon,” Beecham claimed. To soothe Christian sensibilities, the setting was shifted from Judea to Ancient Greece and all Biblical references were removed. Jochanaan (John the Baptist) became simply "The Prophet," and his severed head was replaced by a bloodied sword.

Still the Freudian does have a habit of slipping, come what may, and the repressed insists on returning. As Beecham related in his autobiography, the cast did not play ball with the censors. On opening night,

Gradually I sensed [...] a growing restlessness and excitement of which the first manifestation was a slip on the part of Salome, who forgot two or three sentences of the bowdlerised version and lapsed into the viciousness of the lawful text. The infection spread among the other performers, and by the time the second half of the work was well under way they were all giving in and shamelessly restoring it to its integrity, as if no such things existed as British respectability and its legal custodians.

After two World Wars, opera audiences became more liberal—or at least more blasé. Strauss’s onetime shocker took its place in the standard repertoire alongside The Marriage of Figaro, Carmen, and La Bohème.

When Salome was revived at the Met in 1949 under the baton of Fritz Reiner, the Bulgarian soprano Ljuba Welitsch sang and danced the title role, “her ripe form swathed in flimsy green garments that set off a mop of carrot-coloured hair.” This time, “when the great gold curtains finally swept together, the audience set up a thunderous roar, an ovation that lasted for fifteen minutes.”[1]

New York Times opera critic Olin Downes hailed Salome as “a vital modern opera”:

The music is white hot … Strauss’s use of dissonance, which is now child’s play, but which in 1905, or 1907, was the last word of harmonic writing, is still very effective … It still seizes you. But the whole score, with its inherent banalities intact, remains an astonishingly unified and indestructible whole, which, as of 1949, stands up astonishingly well.

Downes went on to suggest that Salome’s place in the repertoire would be safe until producers began to find it “hopelessly old hat” and “impossible to take seriously. Then it will be interpreted superficially, and begin to sound frayed and of the past.”

Seventy-five years on, Salome seems in no danger of falling out of fashion. That has not stopped producers outdoing themselves in more or less successful attempts to recapture its shock factor. Adam Yegoyan thought it cool to stage the Dance of the Seven Veils as a gang rape for the Canadian Opera Company in 1996. Lydia Steier's production at the Paris Opera in 2022 also climaxed in a mass rape, with the added refinement of having her Salome stand stock still on a pedestal while her stepfather Herod danced around her, removing her garments once by one.

Catherine Malfitano has the distinction of being the first Salome to dispense with the bodystocking and bare her all for art in Peter Weigl’s production at the Deutsch Oper Berlin in 1990. Maria Ewing spectacularly did the same for (her husband) Peter Hall’s production at Covent Garden in 1992—a more than adequate atonement for Thomas Beecham’s bowdlerization in the same house eighty-two years before.

The Met finally caved in 2004. New York Times reviewer Anthony Thommasini couldn’t get enough of “attractive blonde-haired Finnish soprano” Karita Mattila:

Ms. Mattila was so intense, possessed and exposed in the role that she pummeled you into submission.

And I use the word exposed literally. For her slithering and erotic interpretation of Salome's ''Dance of the Seven Veils,'' cannily choreographed by Doug Varone and sensually conducted by Valery Gergiev, Ms. Mattila shed item after item of a Marlene Dietrich-like white tuxedo costume until for a fleeting moment she twirled around exultant, half-crazed and completely naked.

Nowadays exposing the soprano seems to have become par for the course. Among recent interpreters, Mlada Khudoley, Nicola Beller Carbone, and Patricia Racette have all ended Salome’s dance au naturel.

In the end what endures is the music. As Lawrence Gilman told readers of the North American Review back in 1907,

in harmonic radicalism and in elaborateness and intricacy of orchestration [Salome] is [Strauss’s] most extreme performance. His use of dissonance—or, more precisely, of sheer cacophony—is as deliberate and persistent as it is unabashed. The entire score is a harmonic tour de force of the most amazing character—a practically continuous texture of new and daring combinations of tone.

Of the many recordings, Ljuba Welitch’s 1944 Vienna Radio broadcast of the closing scene, conducted by Lovro von Matacic, is hors de concours. In part, as Bryan Crimp writes in his liner notes, this is “because the voice is so youthful.”[2] But only in part. It’s not just the voice, which indeed shines gloriously, but what Welitsch does with it.

Welitsch and Matacic rehearsed the performance with the composer himself, who was by then in his eightieth year. “Richard Strauss was terrific,” Welitsch told an interviewer for the magazine Opernwelt later, “he went through every bar, every phrase with Matacic and me. For example, this ‘Ich habe deinen Mmmmmuuuunnnd geküsst’ (I have kissed your mouth), this desire, he said, must come out in you, it was fantastic.”

Ljuba didn’t disappoint. Especially in that exultant, incandescent final passage. For Jürgen Kesting,

In the 1944 recording, for the climactic phase, on the last syllable of “Jochanaan” … the slenderly sensual voice not only sparkles like a diamond, it burns. What Welitsch has left behind is not only the ominous best rendering or representation of this scene—but the only one ever.

Listen to it, if you dare. Here we really do have the Salome of Strauss’s dreams (or should I say nightmares?)—”a sixteen-year-old princess with the voice of an Isolde."

Act 3 What is this shit?

Salome may have raised the curtain on twentieth-century music, but Strauss grew weary of being portrayed as the torch-bearer for modernism by his opponents and fans alike. As early as 1900 he had confessed to Romain Rolland that

I am not a hero; I haven't got the necessary strength; I am not made for battle; I much prefer to go into retreat, to be peaceful and to rest. I haven't enough genius ... I don't want to make the effort. At this moment what I need is to make sweet and happy music. No more heroisms.

Elektra (1909) took Salome’s dissonance even further, but with Der Rosenkavalier, which premiered in Dresden in 1911, Strauss and his librettist Hugo von Hoffmannsthal offered something completely different—a camp pastiche of Mozart and (Johann) Strauss’s comic operas which the critics panned and audiences loved.

On February 11, 1909 Hofmannsthal had written to Strauss, "My dear Doctor, I have spent three quiet afternoons here drafting the full and entirely original scenario for a new opera, full of burlesque situations and character. It contains two big parts, one for baritone and one for a girl dressed up as a man, à la Farrar or Mary Garden."

Geraldine Farrar wanted too much money. Mary Garden turned down the role of Count Octavian "because it would bore me to make love to a woman." She was referring to the fact that at the beginning of the opera the curtain rises on 17-year-old Octavian in bed with the 33-year-old Marschallin, with whom he had spent the night. Strauss loved to write for the soprano voice, and casting Octavian as a trouser role enabled him to compose some luscious soprano duets and trios.

Der Rosenkavalier was the operatic equivalent of Bob Dylan’s infamous 1970 album Self-Portrait. Griel Marcus began his review of the latter in Rolling Stone with the words “What is this shit?”

Imagine a kid in his teens responding to Self-Portrait. His older brothers and sisters have been living by Dylan for years. They come home with the album and he simply cannot figure out what it’s all about. To him, Self-Portrait sounds more like the stuff his parents listen to than what he wants to hear; in fact, his parents have just gone out and bought Self-Portrait and given it to him for his birthday. He considers giving it back for Father’s Day.

But Richard Strauss had found his operatic métier, and he never looked back. He knew well indeed, he said, that as an art form opera was dead. Wagner was so gigantic a peak that nobody could rise higher. "But," he added, with a broad, Bavarian grin, "I solved the problem by making a detour around it.”

The detour produced a string of Strauss/Hoffmannsthal hits: Ariadne auf Naxos (1912), Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919), Die ägyptische Helena (1928), and Arabella (first performed in 1933). After Hoffmannsthal died in 1929 Strauss turned to the Jewish writer Stefan Zweig for his next opera, Die Schweigsame Frau (The Silent Woman).

By the time Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Strauss was Germany’s pre-eminent living composer. At first he thought he could quietly retreat to the villa in the Munich suburb of Garmisch he bought with the proceeds from Salome until the storm passed.

“I made music under the Kaiser,” he supposedly told his family. “I’ll survive under this lot, as well.” Considering himself above politics, he assured them: “I just sit here in Garmisch and compose. Everything else is irrelevant to me.” He soon discovered that for an artist of his stature, neutrality was not permitted.

Strauss “met frequently with Hitler, Goering, and Goebbels,” recalled Stefan Zweig, “and at a time when even [Wilhelm] Furtwängler was still in mutiny, allowed himself to be made president of the Nazi Chamber of Music.”

Strauss's open participation was of tremendous importance to the National Socialists at that moment. For, annoyingly enough, not only the best writers, but the most important musicians as well had openly snubbed them, and the few who held with them or came over to the reservation were unknown to the wide public. To have the most famous musician of Germany align himself with them at so embarrassing a moment meant, in its decorative aspect, an immeasurable gain to Goebbels and Hitler. Hitler, who had, as Strauss told me, during his Viennese vagabond years scraped up enough money to travel to Graz to attend the premiere of 'Salome,' was honouring him demonstratively; at all festive evenings at Berchtesgaden, besides Wagner, Strauss songs were sung almost exclusively.

The Reichsmusikkammer (Reich Chamber of Music) regulated all aspects of German musical life. Its brief was to make “good German music,” which meant such modernist deviations as expressionism and atonality, together with jazz (“Negro music”), swing, and anything by Jewish composers like Mendelssohn, Mahler, or Schoenberg—not to mention Irving Berlin—were banned. Fortunately Strauss’s years of dissonance were far behind him.

Strauss’s works during his time at the Reichsmusikkammer include the suitably pompous Olympic Hymn for the 1936 Berlin Games. But by the time the hymn was played at the opening ceremony, he had been forced to resign his position. He was already in trouble over his insistence on including Stefan Zweig’s name in the program for the première of Die Schweigsame Frau, when a letter to Zweig in which Strauss criticized Nazi racial politics was intercepted by the Gestapo. Die Schweigsame Frau was canceled after the second performance and banned throughout Germany.

Strauss was undoubtedly vain, loved fame and money, and hoped to use his position at the Reichsmusikkammer to improve the lot of German musicians. But as Zweig makes clear, the composer had other reasons for working with the Nazis too:

To be particularly co-operative with the National Socialists was … of vital interest to him, because in the National Socialist sense he was very much in the red. His son had married a Jewess, and thus he feared that his grandchildren whom he loved above everything else, would be excluded as scum from the schools; his new opera was tainted through me, his earlier operas through the half-Jew, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, his publisher was a Jew.

After 1936 the regime kept Strauss on a tight leash, and his daughter-in-law Alice and grandsons Christian and Richard were hostages for his good behavior. Alice and her sons were harassed during the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938. After Alice’s grandmother Paula Neumann was detained in Prague in 1942, Strauss drove to the gates of Terezín concentration camp to demand her release. He was unsuccessful. Together with twenty-five other relatives of Alice’s, Paula Neumann perished in the camps.

By the time Strauss came to rehearse that incandescent final scene of Salome with Lovro von Matacic and Ljuba Welitsch, he had been living in Vienna for two years. He moved there with Alice and her children in 1942, promised protection by Baldur von Schirach, the Gauleiter of Vienna. The Gestapo arrested Alice together with Strauss’s son Franz in 1944, but Strauss was able to secure their release and allowed to take them back to Garmisch, where they were held under house arrest till the war ended.

The final months of the war hit Strauss hard as he watched opera house after opera house where his works had played—the Lindenoper in Berlin, the Semper in Dresden, the Vienna State Opera house—reduced to rubble and ashes by Allied bombs.

A famous photograph by Lee Miller shows the young Irmgard Seefried singing an aria from Madame Butterfly in the ruins of the Vienna State Opera in 1945. A year earlier, on June 11, 1944, at the outset of her career, Seefried was “a Composer of one’s dreams” in Ariadne auf Naxos, conducted in the same building by Karl Böhm in a special performance to celebrate Richard Strauss’s eightieth birthday.

The performance was recorded. “[Seefried] is in magnificent voice,” writes Ken Melzer,

and ever attentive to the character’s mercurial changes of moods; from frustrated artist, to inspired creator, to an impetuous young man in love (both with his art and, for a bit, with Zerbinetta). The Composer’s final apostrophe to his art is everything it should be, radiantly sung, and brimming with humanity.

Strauss poured his grief into the “solemn, dark, and resigned music from the end of a sorrowing composer’s life” of Metamorphosen, a suite for 23 solo strings composed between 13 March—the day after the destruction of the Vienna Opera House—and 12 April 1945. In its conclusion, Strauss quotes the opening bars of the Funeral March from Beethoven’s Eroica symphony, beneath which he wrote on the final page of the score: “In memoriam.”

A few days after finishing Metamorphosen, he recorded in his diary:

The most terrible period of human history is at an end, the twelve-year reign of bestiality, ignorance, and anti-culture under the greatest criminals, during which Germany’s 2000 years of cultural evolution met its doom.

Listening to Metamorphosen, scored for ten violins, five violas, five cellos, and three double basses, one might well ask “Ist dies etwas der Tod?” (Is this perhaps death?) In keening music of unrelenting ferocity, the 23 strings plumb the depths of sorrow, grief, misery, despair.

Act 4 Ist dies etwas der Tod?

David Bowie’s favorite albums, as listed in Vanity Fair in November 2003, include The Fabulous Little Richard, Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians, John Lee Hooker’s Tupelo Blues, The Velvet Underground and Nico, Charles Mingus’s Oh Yeah, The Fugs self-titled debut album, and Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps—the latter on Woolworth’s Music for Pleasure budget label with Australia’s Ayres Rock blazing red on the cover, which David bought in the late 1950s when he was in his early teens. That MFP recording was my introduction to The Rite of Spring too.

In their time and in their way, all of these were “edgy.” But Bowie’s “one album that I give to friends and acquaintances continually” may come as more of a surprise—

Although Eleanor Steber and Lisa della Casa do fine interpretations of this monumental work, [Gundula] Janowitz’s performance of Strauss’s Four Last Songs has been described, rightly, as transcendental. It aches with love for a life that is quietly fading. I know of no other piece of music, nor any performance, which moves me quite like this.

“At the end of a long and successful career, when a composer still has the power to move his audience with a swansong of such sublime beauty that it takes your breath away—well, you know that work is a masterpiece,” writes Jane Jones:

The words are all warm, wise and reflective with no hint of religious consolation as death approaches, but rather a deeply felt appreciation of the world before leaving. This isn’t some maudlin notion with the benefit of hindsight, although these songs do have a profound sense of longing and melancholy, but the overwhelming effect is one of a feeling of serene peace. It's simply one of the most touchingly beautiful ways for a composer to end his career.

“Strauss clearly is making a final statement, offering a credo of sorts, particularly in the song Im Abendrot (At Sunset), which describes death as a vast, tranquil peace after the weariness of wandering,” agrees soprano Renée Fleming, who has sung Strauss’s cycle more often than any other work in her repertoire.

Strauss did not know that these would be his last songs when he composed them at the age of 84, less than a year before his death. The title was given by his publisher.

In the same way that it is now almost impossible to look at photographer Francesca Woodman’s teenage self-portraits without seeing in them a foreshadowing of her suicide at 22, it is difficult today to hear the Four Last Songs as anything but an envoi. But would we hear them the same way if Strauss had lived ten more years?

“Ist dies etwas der Tod?” is the last line of Im Abendrot (At Sunset), the Alfred von Eichendorf poem that concludes the last of the Four Last Songs in the order in which they are usually performed (although it was actually the earliest of the four to be composed—its conventional placing at the end is for poetic and dramatic effect).

The musical mood could not be more different than that of Metamorphosen. Here the strings soar, the soprano shimmers and shines, the horns softly glow, and the flutes trill in imitation of Eichendorff’s two skylarks nightdreaming as they climb into the sky at dusk. Despite the fact that three of the four poems Strauss chose to set (the others are by Hermann Hesse) ostensibly deal with death, the music makes us feel that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds to leave behind.

When I was much younger I used to love these songs. They moved me as they did David Bowie. But at the age of 73, I am more ambivalent—and the more so, the more I have learned about the circumstances of their creation.

In ill health, short of money, his reputation sullied by his association with the Nazi regime, Strauss and his wife, soprano Pauline de Ahna, left defeated Germany in October 1945 for Switzerland where they lived in hotels. The recent past continued to shadow him.

Between finishing Im Abendrot in Montreux on May 6, 1948 and completing Frühling (Spring) on July 18 in Pontresena, Strauss faced a de-Nazification hearing. In the event, he was cleared of collaboration. He finished Beim Schlafengehen (Going to Sleep) in Pontresina 17 days later, and September in Montreux on September 20.

There are undoubted moments of astonishing beauty in these works. The violin solo before the lines “Und die Seele unbewacht/will in freien Flügen schweben” (And the unguarded soul/wants to float in free flight) in Beim Schlafengehen is breathtaking.

But—for me at least—it also brings back another violin solo, in Janáček’s opera Jenůfa, ascending from the orchestra pit up to the gods where I was sitting in Glasgow’s Theatre Royal way back when—only, that solo came at the climax of Kostelnička’s aria Co chvila (A Moment) in which the sextoness resolves to kill her daughter Jenůfa’s illegitimate baby.

The violin ratchets up the tension unbearably as Kostelnička snatches up the child and rushes out into the icy night. Compared with this, the violin solo in Beim Schlafengehen feels like cheap artifice.

And this is my problem with the entire cycle. Not least, with those trilling skylarks with which Im Abendrot, and the cycle, concludes. What kind of shit is this? I ask. Especially coming from the composer whose scandalous, vulgar, cacophonous Salome lifted the curtain on twentieth-century music?

When all is said and done, the poems are trite, the sentiments shallow, the music less a coming to terms with death than a determined looking away from it, cloaking its terrors in a blanket of saccharine loveliness with not a dissonant note to disturb the reverie.

The cycle is an ersatz envoi, a camp masquerade, fit to stand alongside Frank Sinatra’s My Way and John Lennon’s Imagine as an enduring memorial to the middlebrow. There can be few better examples of kitsch as Milan Kundera defines it—“the need to gaze into the mirror of the beautifying lie and to be moved to tears of gratification at one’s own reflection.”

The Four Last Songs bear the same relation to Metamorphosen as Der Rosenkavalier does to Salome and Elektra. Richard is up to his old tricks again. Taking a detour.

Or is he?

As I sat down to write this piece, I listened for the first time in years to Gundula Janowitz’s rendition of the Four Last Songs, the one recommended by David Bowie.

“This recording is frequently cited as a favourite for obvious reasons,” writes Ralph Moore in his review of forty-six of “the most notable” renditions of the cycle—there have been many more, for what soprano worth her salt could resist the challenge of such beauty? He praises

the silvery, soaring ecstasy of Janowitz’ lirico-spinto soprano, the mastery of Karajan’s control of phrasing and dynamics and the virtuosity of the Berlin Philharmonic at their peak. Janowitz’ voice has an instrumental quality which blends beautifully with the orchestra. The rapt quality essential to these songs making the necessary impact is present throughout; the requisite trance-like atmosphere is generated without risking torpor or languor. For me, as for many others this is as close to a flawless recording of these masterpieces as can be achieved.

I agree. Janowitz strikes the perfect balance between the lightness of a Lisa Della Casa or Elizabeth Schwarzkopf and the sumptuousness of Jessye Norman, whose recording, to my ears, drowns under the weight of its own splendor. Norman’s Im Abendrot clocks in at a stately 9 minutes and 56 seconds, where Janowitz is done and dusted in 7:09.

By chance, as I was listening to Janowitz my laptop was open on Gustave Moreau’s 1874 oil painting Salome Dancing, aka Salome Tatooed, which I had downloaded while searching for possible illustrations for this essay. More high camp. On the face of it, Moreau’s salacious painting and Strauss’s sublime music couldn’t be further apart.

This “fortuitous meeting of two distant realities on an inappropriate plane” (Max Ernst) produced a remarkable synesthesia. Call it hasard objectif. Letting the music wash over me, I continued to gaze—with, no doubt, a very male gaze—at Moreau’s Salome.

And Salome returned my gaze: while her head is modestly averted, the eyes tatooed beneath her breasts look full frontally into yours.

Strauss’s lush orchestration mirrors all the dark richness of Moreau’s colors, the glowering reds, the glints of blue and gold. Janowitz’s voice, soaring effortlessly over the orchestra, is the perfect aural counterpart to Salome’s luminous dancer, exposed and vulnerable and yet commanding the rapt attention of all.

I briefly wondered what might happen if we were to stage the final scene of Salome to the accompaniment of the Four Last Songs, or substituted the words “Ich habe deinen Mund geküsst, Jokanaan” for “O weiter, stiller Friede! so tief im Abendrot” (O vast, silent peace, so deep in the sunset) in Im Abendrot. The idea is not so preposterous.

After all, a mere four years separated Strauss’s Four Last Songs from that definitive recording of the final scene of Salome for Vienna Radio in 1944, when the old master coached Ljuba Welitsch on how to pour every last ounce of desire into the princess’s triumphant “Ich habe deinen Mmmmmuuuunnnd geküsst, Jokanaan.”

Somewhere, I’m sure, Richard Strauss is grinning that broad Bavarian grin.

[1] Frank Merkling, sleevenotes to Ljuba Welitsch, Final Scene from Salome and Other Arias, CBS Legendary Performances 61088.

[2] Ljuba Welitsch, soprano. The HMV Treasury, HLM 7006